Born in Pamiers in 1765, Claire Lacombe (sometimes nicknamed Rose) burst onto the revolutionary scene in 1792 – and promptly disappeared again in 1795. Her story is particularly interesting because she was one of only a few working-class women whose individual impact on the revolution was significant. She and Pauline Léon founded the society of Républicaines-révolutionnaires, which played a role in the fall of the Girondins, and was undoubtably a force to be reckoned with. Despite the very short period in which Lacombe was active, she deserves to be remembered for her fearless campaigning, and her strident attitude towards women’s rights.

Little is known of her early life, as is so often the case with historical figures from the lower classes. Born as the legitimate daughter of Bertrand Lacombe, a merchant, and Jeanne-Marie Gauché on 4th March 1765, Lacombe was an actress, though by all accounts not a particularly successful one, and travelled the country in this profession.[1] At the outbreak of revolution in 1789, she was working as a comedienne in Marseilles. She was described as being “five foot two, with chestnut brown hair and eyebrows, brown eyes, an aquiline nose, an ordinary mouth and a round face”.[2] According to both Lacour and Lairtuillier, as well as to an anonymous archival source, the reason for Lacombe’s professional struggles could well be her political beliefs.[3] This is certainly supported by an anecdote Lacour recounts, in which Lacombe was refused a part and proceeded to organise un fracas that continued until the director relented and allowed Lacombe the part. Likely because of her revolutionary sentiments and her outspoken nature, it appears she struggled to find work in Toulon in 1791, and thus headed to Paris.[4]

“The din didn’t stop until the director came out and satisfied us by consenting to the actress” – Gerard Anton von Halem, Paris en 1790: voyage de Halem (3rd letter)

It is worth noting that in this period, being an actress was only a small step above being a prostitute: it was a disreputable occupation, one which brought contempt and ridicule, and this makes Lacombe’s significance all the more remarkable. Prostitutes were often known as femmes publiques (public women), which indicates rather well the contemporary attitudes towards women outside the home: in typical Rousseauian fashion, women were expected to limit themselves to the domestic sphere, and only fallen women made themselves known outside it.[5] Claire Lacombe fit quite firmly into this category of women – an unmarried actress, who lived alone with a man she was not related to, who involved herself in politics, and even protested and armed herself. In many ways, this was to be her downfall, but for a time it made her a truly remarkable individual, and certainly worthy of study.

In July of 1792, an as yet unknown Claire Lacombe read a speech to the Legislative Assembly calling for the replacement of Lafayette as the head of the army and offering to personally combat tyrants. She was dressed in an amazone, a riding habit with a deliberately masculine cut, a favourite of Théroigne de Méricourt. This address is particularly interesting, as Lacombe herself displayed period typical internalised misogyny when she offered to play an active role “in combating the enemies of the Fatherland”, but only because she was a childless, single woman – in the same breath she condemned mothers who would follow her. Whilst to modern sensibilities this might seem outrageous, condescendingly instructing some women to stay at home quietly because they are not fit for revolutionary action, it was still an extremely forward-thinking attitude in its time. This much is apparent from the response of the assembly, who granted her the honours of the session, whilst praising one “made more for softening tyrants than for struggle against them”.[6] Here, perhaps, is the first indication of the attitudes that Lacombe faced – patronising praise of a woman who had the right idea, but should really be at home raising a family and leaving the important matters to the men. This is the first record of Lacombe in the capital, and it is clear that from the very beginning she was unwilling to be a bystander. She was living off her savings, completely independently of men, which was a rare feat for an ordinary woman, and she regularly attended meetings of the Jacobin club.[7]

However, Lacombe’s first real outing on the revolutionary stage was during the events of August 10th, 1792: a mob descended on the Tuileries and demanded that the King be deposed – they were successful. Many women took up arms in the fighting, and three won civic crowns: Louise “Reine” Audu, Théroigne de Méricourt, and Claire Lacombe.[8] Lacombe was wounded in the struggle (whether shot or stabbed in the arm, reports differ), but seemed unperturbed. Just two weeks later she gave an address to the legislative assembly, and was awarded the honours of the session.

“On August 10 she appeared as an Amazon and demanded from Westerman that he allow her to serve; she was put at the head of some men, and she received a dagger wound.” – Roussel and Lord Bedford, in Le Chateau des Tuileries (35)

These early honours seem to have encouraged Lacombe, for in May 1793 she and Pauline Léon registered La Société des Républicaines-Revolutionnaires with the authorities at the commune.[9] This society was to prove extremely important, and is the main reason that Lacombe was so significant.

The society allied itself closely with the Jacobins, in whose library they met, and fiercely opposed the Girondins. All members vowed to “execrate the scoundrels Roland and Brissot and the whole gang of federalists and … undertook the defence of all persecuted patriots such as Robespierre [and] Marat”.[10] Members prowled the streets in cockades and bonnets rouges, brandishing various weapons and searching for enemies of the revolution, and frequently whipping or beating those they deemed unpatriotic. A group of society members attacked Théroigne de Méricourt, whose unlikely saviour Marat managed to deflect attentions.[11] Shortly afterwards, a deputation of enragés and society members, including Lacombe, demanded the formation of revolutionary courts across the country to arrest and try suspected counterrevolutionaries. This seems to have been the last straw for the beleaguered Girondins: previously less definitively opposed to women’s rights, they now denounced the “depraved societies”, with Buzot claiming that these were “monstrous women who have all the cruelty of weakness and all the vices of their sex”.[12] Here lie the roots of the conflict which would later appear between the Jacobins and the society: as the women grew increasingly militant and bold, they began to threaten the Jacobins and Montagnards. Even if their aims were aligned, they were a danger to the status quo and to those in power. They were still useful, however, and this made them vital in the coup that meant the end of the Girondins.

When the Girondin deputies were denounced and expelled in June, it was the society who waited outside the meeting chamber to prevent them escaping, and were reported to be bloodthirsty and furious.[13] Despite the obstacles, the society is a perfect example of women exerting concrete influence on the political process: they may not have been part of the assembly, but their petitions were numerous and largely well-received, and they were seen by the Girondins, police, spies and others as an important force.

“Armed women held the deputies captive lest they display a prearranged signal; one of them, pursued by five or six of these shrews, was forced to jump from a casement window” – A. J Gorsas, Précis rapide des événements qui ont eu lieu á Paris dans les journées des 30 et 31 mai, premier et 2 juin 1793

However, all was not well within the society. Some members were unhappy with the attitude taken by Léon and Lacombe towards Robespierre, and rebellious members even denounced Leclerc to the Jacobins.[14] Several members of the society appeared in front of the assembly in September to denounce Claire Lacombe in no uncertain terms, and the Jacobins were quick to follow, condemning the entire society but Lacombe in particular. Her living arrangements were also brought into question in the September 16th session of the Jacobin club: as much because of Leclerc’s supposed aristocratic heritage as because of the immorality of an unmarried woman living with an unrelated man.[15] Lacombe’s statement to the society in response to her accusers is well worth reading, as it perfectly illustrates her intelligence and determination. She clearly sees the dangers ahead for her and the society as a whole, and makes a particularly astute comment on the way in which various politicians escaped their own guilt: “Beware, Robespierre! I perceive that those who have been accused of corrupt practices believe that they will escape these denunciations by accusing those who denounce them of having spoken ill of you.”.[16] Her speech reveals an intelligent woman and a formidable opponent, but one who was nonetheless crushed by the fragmentation of her society and by her imprisonment.

By the end of October 1793, the society was prohibited and disbanded, and many of its members imprisoned. What happened in these few short months to cause this? For Godineau, the answers lie in the events surrounding the death of Marat. For some time after Marat’s assassination the society was entirely focused on memorialising him and his death, as a symbolic representation of the threat to the revolution, and as a result they withdrew almost entirely from political agitation. When they re-entered the political arena, they had re-aligned themselves, away from the Jacobins and closer to the enragés, in part due to the close relationship between Leclerc (one of the enragé leaders) and both Claire Lacombe and Pauline Léon.[17] This move away from the Jacobins (and their increasing opposition to Robespierre) created friction between the society the Jacobins, and increased many men’s fears of the society and their power. The death knell of the society, and indeed of Lacombe’s political career, came with the rupture between the society and the Jacobins.

One might think that Lacombe’s experiences with the Jacobins would be enough to persuade her to keep a low profile for a while, but this was not the case. She and the other société members managed to pressure the assembly into passing a measure requiring all women to wear the tricolour cocarde, whereas previously only men need wear it. This caused an outcry from the respectable market women of Les Halles, who already opposed the society on principle, and were outraged by the new law.[18] They saw politics as an exclusively male domain, and involved themselves only when the threat of starvation compelled them to.

Towards the end of October, a group of drunken market women stormed a meeting of the society, attacked the members and attempted to destroy the society’s symbols. One man, intervening on the behalf of a citoyenne who was being beaten with a wooden clog, was stabbed.[19] Despite the fact that the society was in fact the victim of this attack, it provided the national assembly with a timely excuse. On the 30th October 1793, the National Convention banned all women’s organisations, in a move deliberately calculated to crush the société des républicaines-révolutionnaires. Amar’s address on the 28th October described thousands of women gathering in Les Halles to protest against the actions of the society, and stated that the ward requested the abolition of female societies. This motion was passed with just one dissenter: one citoyen Chalier spoke out to say “Unless you are going to question whether women are part of the human species, can you take away from them this right [to assemble peaceably] which is common to every thinking being?”. It seems that the convention had already made up their mind, as the measure was passed. Indeed, Amar justified it as “related essentially to morals, and without morals, [there is] no republic.” – here is a clear example of the revolutionary discourse which inextricably linked feminine virtue (defined as sexual containment, and a purely domestic life) and the wider civic virtue.[20] If women kept to their proscribed roles and remained at home, the republic would prosper; if they did not, it would perish.

A few former members of the society attempted, in vain, to appeal the law that had disbanded their club, but were met with scorn. They even appeared before the General Council of Paris on the 17th of November, but were again attacked for daring to express political sentiments.[21] The final blow for the society was the rift between Lacombe and Léon, which had been brewing for some time. It is obviously hard to tell why exactly Léon and Lacombe grew apart, but many have theorised it is related to Léon’s relationship with and subsequent marriage to Leclerc (in November 1793), who had been living with Lacombe for several months and who, allegedly, had been conducting an affair with her. This is certainly supported by accounts of a very public confrontation between the two in a meeting of the society, in which Léon accused Lacombe of sleeping with Leclerc, and Lacombe supposedly admitted it.[22] Hereafter, both Leclerc and Léon seem to have taken a backseat, and Lacombe was limited by the law forbidding female organisations, and by the fierce distrust and dislike she faced from members of the assembly.

“Do you remember the famous Lacombe, the renowned actress and president of the fraternal society of revolutionary amazons? She has become a shopkeeper providing small pleasures to prisoners of the state, her companions in misfortune … now she is simple, neat as a pin, gracious to the buyers, she is nothing more than a small, modest, bourgeois woman” – memories of Lacombe’s fellow prisoner, Joachim Vilate, Les mysteres de la Mere de Dieu dévoilés: 3 volumes des causes secretes de la revolution du 9 au 10 thermidor (41)

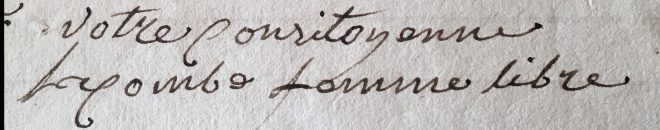

Both Lacombe and Léon were imprisoned in 1794, although Lacombe’s imprisonment lasted eleven months longer than Léon’s.[23] Godineau theorises that this is due to her refusal to renounce the government, or to embrace the new government after Robespierre’s fall. She signed every letter from prison “Citoyen Lacombe, femme libre”, indicating her refusal to bow to the pressure. Whatever the reason for her extended captivity, her friends remarked that it left her changed: “her health and spirits were strangely fatigued”. Several of her friends, most notably Victoire Capitaine, wrote to the Comité de la Surété Generale in an attempt to obtain her release, though it is not clear if this influenced their eventual decision. Upon her release in August 1795, Lacombe’s actions become rather less easy to discern. It seems she attempted to restart her acting career in Nantes, receiving a contract to play leading roles – “queens, noble mothers, great coquettes”, and interspersed occasional stints in the theatre with spells in prison. The last record of her is from May 1798, when she seems to have returned to Paris with a companion, an actor who was likely her lover, and owed her landlady 386 livres.[24] There the record ends. There is no knowledge of her later years or her death. This is not entirely uncommon amongst lower class women in this period, and is in itself rather telling. The fact that Lacombe left politics entirely, despite the urging of several of her friends in Paris, reveals the fatigue that many women displayed.[25] Thérésa Tallien did something similar (albeit in a far more comfortable setting), retiring to Switzerland and doting on her many children and grandchildren, rarely leaving her estate. Lacombe’s life followed a similar pattern to before the revolution, and as was the case for all French women, very little had changed or improved in their legal rights or status. This may go some way towards explaining why women such as Lacombe, and the others in this project, are so often overlooked: there was almost no measurable change in women’s lives. They were still subject to their husbands and fathers, still suffered inequality in the eyes of the law, and were still confined largely to the private sphere. However, it is important to note that this doesn’t diminish the significance of women like Lacombe and their actions.

Claire Lacombe spent at least three years fighting tooth and nail for her rights, and for those of her fellow citizens, both male and female. She faced derision, imprisonment, even death, and was rarely accorded the respect she deserved. At a time when rights were being demanded and seized by French men, she attempted to do the same for French women. She organised a society of fierce and dedicated women who were clearly organised and powerful enough to pose a threat to Robespierre. She spoke eloquently and persuasively to an assembly of men, most of whom would have preferred her to stay home. She supported herself financially and lived without depending on a man, and rose above the slights to her reputation. Here then, was a formidable and committed woman who deserves to be remembered for her actions, her passion, and her determination.

“The majority of female militants from the French Revolution are perfect nobodies about whom we know nothing but their identity. This hasn’t stopped them from playing a role… a rather fruitless role, it’s true, and utterly short-lived, but despite this, crucial in women’s history, in French revolutionary history, and in human history.” – Francoys Larue-Langlois, Claire Lacombe: Citoyenne révolutionnaire (130)

[1] Francoys Larue-Langlois, Claire Lacombe: Citoyenne révolutionnaire (Punctum, 2005) : 7

[2] Marie Cerati, Le club des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires (Paris : éditions sociales, 1966) : 37

[3] Léopold Lacour, Trois femmes de la révolution : Olympe de Gouges, Théroigne de Méricourt, Rose Lacombe (Plon-Nourrit, 1900) : 320

[4] Francoys Larue-Langlois, Claire Lacombe: Citoyenne révolutionnaire (Punctum, 2005) : 13

[5] Lucy Moore, Liberty: the lives and times of six women in Revolutionary France (Harper Perennial, 2006): 55, 348

[6] Ibid, 189

Darline Gay Levy, Harriet Branson Applewhite, Mary Durham Johnson, Women in Revolutionary Paris 1789-1795 (University of Illinois Press, 1979): 156-7

[7] Dominique Godineau, Citoyennes Tricoteuses: les femmes du peuple á Paris pendant la Révolution Francaise (Alinéa, 1988) : 122

Archives Nationales (T 1001, 1-3 d. Lacombe, Archives Parliamentaires 47, p144)

[8] ibid

[9] Darline Gay Levy, Harriet Branson Applewhite, Mary Durham Johnson, Women in Revolutionary Paris 1789-1795 (University of Illinois Press, 1979): 149

[10] Lucy Moore, Liberty: the lives and times of six women in Revolutionary France (Harper Perennial, 2006): 55, 191

[11] Ibid, 192-3

[12] Ibid

Candice E Proctor, Women, Equality, and the French Revolution (Greenwood Press, 1990): p155

[13] Darline Gay Levy, Harriet Branson Applewhite, Mary Durham Johnson, Women in Revolutionary Paris 1789-1795 (University of Illinois Press, 1979): 154

Dominique Godineau, Citoyennes Tricoteuses: les femmes du peuple á Paris pendant la Révolution Francaise (Alinéa, 1988) : 138

[14] Lucy Moore, Liberty: the lives and times of six women in Revolutionary France (Harper Perennial, 2006): 229

[15] Darline Gay Levy, Harriet Branson Applewhite, Mary Durham Johnson, Women in Revolutionary Paris 1789-1795 (University of Illinois Press, 1979): 179, 183

[16] Ibid, 186

Lucy Moore, Liberty: the lives and times of six women in Revolutionary France (Harper Perennial, 2006): 234

[17] Dominique Godineau, Citoyennes Tricoteuses: les femmes du peuple á Paris pendant la Révolution Francaise (Alinéa, 1988) : 153

[18] Lucy Moore, Liberty: the lives and times of six women in Revolutionary France (Harper Perennial, 2006): 234

[19] Ibid, 236

[20] Darline Gay Levy, Harriet Branson Applewhite, Mary Durham Johnson, Women in Revolutionary Paris 1789-1795 (University of Illinois Press, 1979): 213-17

Réimpression de l’Ancien Moniteur, vol. 18 p298-300

[21] Lucy Moore, Liberty: the lives and times of six women in Revolutionary France (Harper Perennial, 2006): 239

[22] Ibid, 230

[23] Francoys Larue-Langlois, Claire Lacombe: Citoyenne révolutionnaire (Punctum, 2005) : 129

[24] Dominique Godineau, Citoyennes Tricoteuses: les femmes du peuple á Paris pendant la Révolution Francaise (Alinéa, 1988) : Appendix 3

[25] Francoys Larue-Langlois, Claire Lacombe: Citoyenne révolutionnaire (Punctum, 2005): 130